Curator’s blog: the Hummingbird Clock

"One of the most beautiful objects on display here is the bird pendulum clock, a timepiece from that romantic era when people still took the time to look at the clock, listen to it and enjoy it.“

This is how an item from the Polygoonjournaal newsreel from 1958 describes the “Hummingbird Clock” (cat. no. 0049). At that time, the clock was already a highlight of the newly opened Museum van Speeldoos tot Pierement, later renamed Museum Speelklok.

Since 1958, the clock has charmed visitors almost daily with its movements and sounds. The workings of the clock are not immediately visible or audible, nor is the history behind it. Who was it made for? What kind of person was the clock’s maker, Blaise Bontems, and what other pieces did he make? In this blog post, junior curator Axel Schering delves into the history behind the “Hummingbird Clock” and its maker to find answers to these questions.

About the ‘Hummingbird Clock’

Unfortunately, it is not known who owned the Hummingbird Clock. However, there is a clue to its history on the back of the clock’s base: a sticker from the Krijnen Brothers Art Dealers in Utrecht. In 1949, the brothers moved their business from Nijmegen to Utrecht; the trade register mentions the closure of the business in 1969. It is possible that Gebr. Krijnen were the penultimate owners or that they acted as intermediaries between a previous owner and the museum – but we cannot say for certain.

How does the clock actually work? The base houses the technical heart of the clock. The movements of the hummingbirds and tanagers are controlled by guides that run over a series of rotating cam discs. The “flying” hummingbirds are mounted on fast-moving metal arms that turn from one hollow branch to another. The waterfall is actually a rotating rod of cut crystal. The technique for the birdsong is surprisingly simple: two bellows at the bottom of the base blow air past a tongue. There is a separate spring for the movements and the bird sounds.

The “Hummingbird Clock” was manufactured around 1870. Although Blaise Bontems and his employees made most of it, parts of the clockwork and cylinder player were sourced from other manufacturers. Japy Fils supplied the clockwork. The cylinder player by Josef Olbrich from Vienna is not the original player. Of the two melodies it plays alternately, one is well known: the aria “Caro nome che il mio cor” from Giuseppe Verdi’s famous opera Rigoletto (1851).

Two crafts come together

But who was Blaise Bontems (1814-1893), the maker of the clock? How did he come to make mechanical birds, in this case in combination with a timepiece? The answers to these questions lie in his early years.

Bontems grew up in the French village of Le Ménil, located in a southern valley of the Vosges. At a young age, he was introduced to the craft of bird taxidermy. Initially, he did not make this his profession; he apprenticed with a clockmaker. During his training, he came across a snuff box with a mechanical bird. Although he was amazed by the tiny mechanism, he was disappointed by the mechanical song – it did not sound very realistic. He decided to improve it; he went into the nearby woods, listened to the song of nightingales, and adapted the singing mechanism accordingly. The next morning, his employer was stunned: it sounded as if a real nightingale was filling the workshop with song…

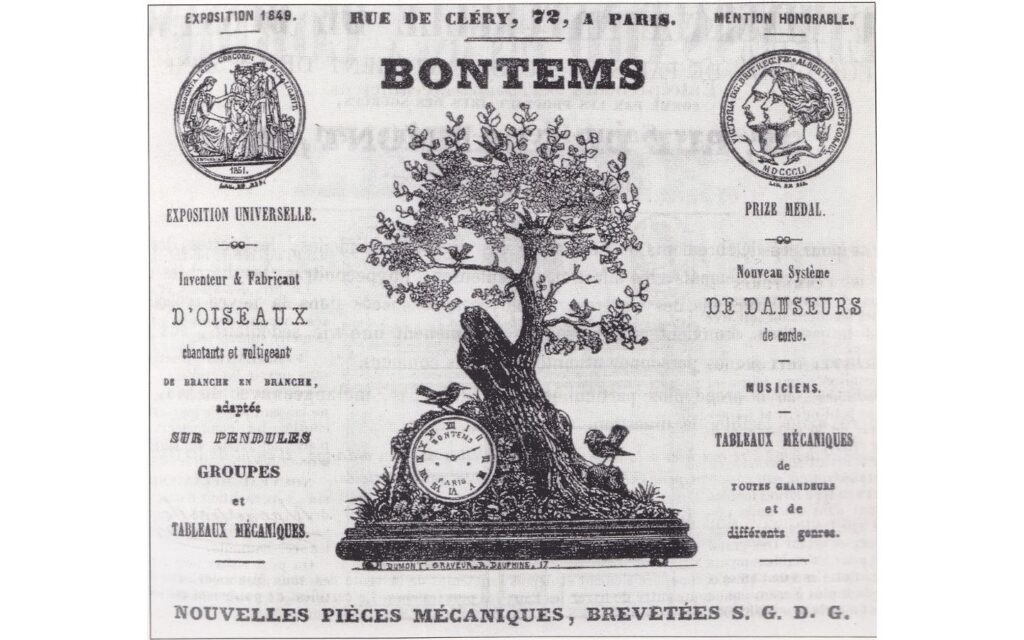

After several years of making a name for himself in the manufacture and sale of mechanical birds, Bontems decided to start his own business. He moved to Paris in 1849 and settled on Rue de Cléry in the Le Marais district (literally “the marsh”). In the second half of the nineteenth century, this district was considered the centre of automaton construction, and many illustrious manufacturers such as Alexandre Théroude, Jean Marie Phalibois, Gustave Vichy and Léopold Lambert produced a staggering number of automaton figures in all kinds of variations there – but initially no mechanical birds. Bontems had found a niche – so niche, in fact, that he was initially listed in the trade register under both “horlogers” (watchmakers) and “naturalistes” (taxidermists). Given his training as a watchmaker, it is not surprising that Bontems also made his birds part of clocks.

International clientele

Bontems’ market had a strong international character. His pieces were sold to cities such as Moscow, Alexandria and Constantinople, and – outside many European states – countries and colonies such as Australia, India and Canada. Some notable customers were Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and the artist Rosa Bonheur. The accounts also mention a seemingly endless number of people from higher circles, who together form a long procession of princes, barons, marquises, generals, bankers, ministers, deputies, diplomats and vice-consuls.

In 1867, journalist Henri Nicolle visited Bontems’ shop at the Paris Exposition Universelle (world exhibition). He reported on the international clientele: “The English are very fond of these pieces. […] India and the Far East express the greatest admiration for Monsieur Bontems’ birds.” According to Nicolle, the Chinese Emperor Xianfeng also owned a Bontems bird, which – according to the following anecdote – became French war booty in the Second Opium War: “The Emperor of China had one, but this only became clear when Peking was captured: the bird was one of several objects taken from the [Old] Summer Palace to be sold at auction in the Salle Drouot [an auction house]. However, the journey had severely damaged its voice; the maker was consulted, who, it is assumed, was rather proud to recognise the golden cage with enamelled panels as one of his creations […].”

Bontems in Museum Speelklok

Finally, it is worth mentioning the other Bontems pieces in Museum Speelklok’s collection. Not many visitors will know that there is also a “Small Hummingbird Clock” in the museum. This is displayed in the tall cabinet with automata in the Museum Expedition, and is significantly simpler in size and design: a smaller tree, no sea with a ship, and the clockwork is – for lack of a spacious base – embedded in the miniature landscape. A very similar piece appears in an advertisement by Bontems from 1858.

In addition to these two bells, the museum also has several caged birds from Bontems; most cages house one bird, but there are also some that contain two or even three birds. All the cages are equipped with a more realistic song than the two bells: whereas the bells only have bellows that blow air past a metal tongue, the bird cages contain a piston flute with a programme of songs recorded on a cam disc. The piston flute and cam disc allow for smooth ascending and descending tone sequences, which – unlike a series of pipes, each with a fixed tone – makes the sound more realistic.

The Hummingbird Clock (cat. no. 0049) will be on temporary display from 12 February to 7 June 2026 in the exhibition BIRDS – Curated by The Goldfinch & Simon Schama, at the Mauritshuis in The Hague.

Want to take a closer look at a Bontems birdcage online? Visit our homepage and scroll down to the gallery!

Sources

Bailly, Christian, en Sharon Bailly. Automata. The Golden Age, 1848-1914. Sotheby’s Publications, 1987.

Bailly, Sharon, en Christian Bailly. Oiseaux de Bonheur, Tabatières et Automates / Flights of Fancy, Mechanical Singing Birds. Antiquorum Editions, 2001.

Bloemendal, Philip (voice-over). “Kijkje in het museum van Speeldoos tot Pierement (1958).” News item, Polygoon-Profilti Productie, 1958. Uploaded on 27 August 2008 by Nederlands Instituut voor Beeld & Geluid. YouTube, 1 min., 40 sec. www.youtube.com

Kamer van Koophandel in Utrecht: Trade Register 1921-1982, file number 17689. Het Utrechts Archief.

Nicolle, Henri. Les jouets: ce qu’il y a dedans. E. Dentu, 1868.